Aging Politicians Are Only Going To Get More Common

Aging Politicians Are Only Going To Get More Common

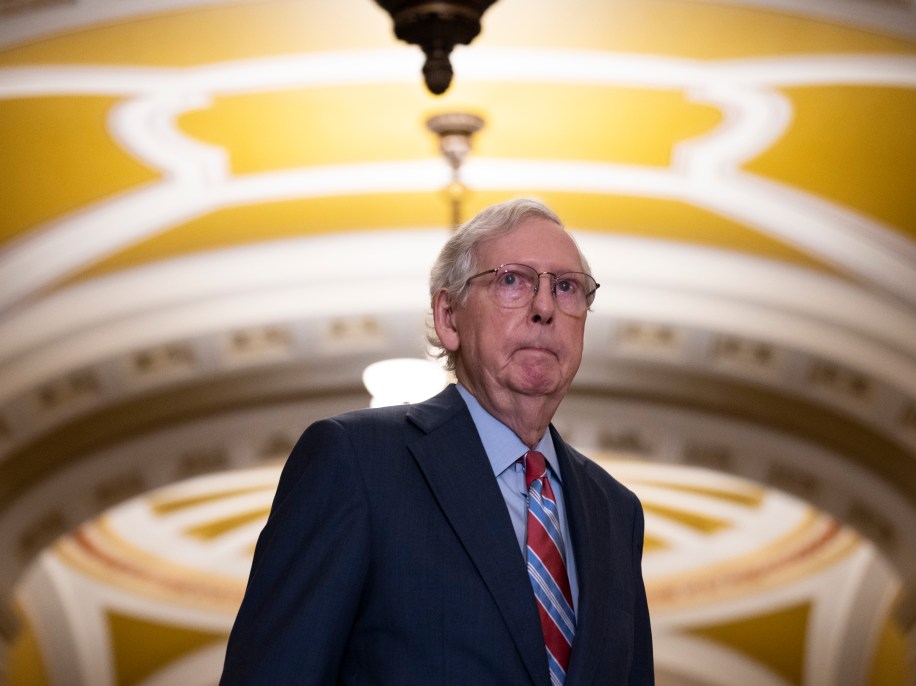

Drew Angerer / Getty Images

Presidents are getting older and older. Former President Donald Trump was the oldest person to assume office when he was sworn in on Jan. 20, 2017, and President Biden broke that record four years later. If either is elected again next year, at ages 78 and 81, respectively, they will be older than the previous record holder, Ronald Reagan, was when he left office at the age of 77.

The possibility of an octogenarian on the presidential ticket is worrying many Americans — perhaps because it’s not just the presidency that’s aging. The current Congress, with a median age of 65 in the Senate and 58 in the House, is the oldest in history. Last week, when Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, 81, seemed to freeze while speaking for the second time in two months, there were renewed calls for him to step aside, and 90-year-old California Sen. Dianne Feinstein has been under similar scrutiny after a series of health issues. Former U.N. ambassador Nikki Haley, who is 51 and running for the Republican nomination, has called for competency tests for candidates older than 75, and her opponent Vivek Ramaswamy, a 38-year-old entrepreneur, has said it’s time for a new generation to step up and lead.

Voters are worried about the age of candidates and elected officials, especially when it comes to Biden. The vast majority of American adults, 77 percent, say he is too old to be effective for another four years, according to an AP-NORC poll in August. Fifty-seven percent of registered voters thought age severely limited President Biden’s ability to do his job in an Economist/YouGov poll from August. Similar questions were asked about Feinstein and McConnell, about whom 60 percent said the same.

But will voters actually start rejecting candidates because of their age? There are plenty of reasons why older politicians continue to hold the levers of power — and the structure of our political system makes it hard to force them to let go, even as Americans’ concerns about the country’s aging political leadership mount. That’s why Americans may continue to support older politicians when they’re in the voting booth, even as they say they prefer a younger leadership cohort.

Americans are increasingly worried about politicians’ age

Biden might be the oldest president in U.S. history, but worries about whether presidents are too old for the job have been floating around for a while. Americans became increasingly worried about Reagan’s age during his tenure. At the start of his second term in 1985, 33 percent of respondents in an ABC/Washington Post poll said Reagan was too old to be president, but by 1987 that number had risen to 42 percent. And a January 1987 poll from Louis Harris & Associates found that 48 percent of respondents agreed with the statement that Reagan was getting too old to be president.

In the modern era, presidents have traditionally released details about their health, and the public has demanded transparency, because the job is physically and mentally demanding and voters want to ensure that the person they elect is the one doing it. Anxieties about that have a basis in past events: President Woodrow Wilson was able to hide the effects of a stroke in 1919 from most of the American public, and his wife, Edith, essentially acted as de facto president until his second term ended in 1921. Later, in 1967, the ratification of the 25th Amendment outlined what should happen if a president died or became incapacitated.

But presidents haven’t always been forthcoming with information. In the absence of diagnoses, voters have often relied on outward signs that their candidates might be unable to do their jobs. Perhaps the most obvious is a candidate’s age, simply because we face the greater chance of serious medical problems and death the older we get.

But in practice, it’s hard to draw bright lines — in part because age is far from a perfect proxy for health. Some older politicians are perceived as more capable than others: Thirty-four percent of voters thought the age of Sen. Bernie Sanders, who is almost 82, severely limited his ability to do his job in the August Economist/YouGov poll, and 28 percent said age would limit Trump’s ability to be president if he were elected again. Those differences suggest that it’s not just ageism, but the specific health conditions of some politicians being reported in the media that voters are responding to; or, in Biden’s case, reporting on every stumble on the stairs to Air Force One.

The health conditions that can come with age, even chronic ones that require accommodations, don’t necessarily mean that elected officials can’t effectively serve, either, which speaks to a broader issue on how voters make assumptions about candidates’ fitness for office. For example, people with physical and mental disabilities are underrepresented in government, with only 1 in 10 elected representatives having a disability, while nearly 16 percent of adults in the overall population have one, according to a study from Rutgers University. As Pennsylvania Sen. John Fetterman’s campaign showed, candidates can face discrimination when disabilities are conflated with cognitive ability. The need for accommodation doesn’t mean an elected representative is unable to work. “You also don’t want to lose the potential contributions of somebody who is older but is quite talented and also now has the benefit of experience to bring to the table,” said James M. Curry, a political scientist at the University of Utah.

Some voters, though, think we should have clearer rules about when a politician is too old to serve. Sixty-seven percent of respondents strongly or somewhat supported an age limit for serving in the Senate in a YouGov/UMass Amherst poll from June, and 58 percent of adults thought age limits for serving as president would be a good idea in a Marist poll from last November. Sixty-eight percent of respondents favored mental competency tests for candidates over 75 in a YouGov/Yahoo survey from February. A plurality, 48 percent, think the job of president is too demanding for someone over 75, according to a CBS/YouGov poll from June. And overall, Americans’ preference for younger leadership is clear: About half of Americans think the ideal age for a president is someone in their 50s, according to the Pew Research Center.

The risk of a politician becoming unable to do their job isn’t the only worry that might be fueling these perceptions. The age of voters and the members of Congress they elect means that programs and issues important to older voters, from Social Security to elder abuse, are more likely to get attention than issues more important to younger voters, like student loans.

“I think the biggest reason that younger Americans want younger lawmakers is they feel they’re not well represented by older Americans, both from a standpoint of the things that older representatives might focus on or talk about that are different from what a younger candidate might talk about,” but also because, like all Americans, they want to see themselves represented in government, Curry said. Younger Americans are missing that representation now. “It makes them less satisfied with their representative government and less satisfied with their democracy,” he said.

It’s also possible, though, that despite what they say, voters prefer reelecting someone with experience and seniority. “The Constitution sets minimum ages for the presidency and for the U.S. House and U.S. Senate, but it doesn’t set a maximum,” said William J. Kole, the author of the forthcoming “The Big 100: The New World of Super-Aging.” “And you have to believe that the Framers clearly valued experience over youth. That’s part of our DNA in some ways, politically.”

But our system could ensure that older politicians stay in power

There are a few factors contributing to our aging politics, and they provide a hint as to why voters are choosing older candidates despite saying in polls that they would prefer younger ones. The first is simple demographics. Older voters are more likely to vote and are more likely to choose candidates closer to their age. Younger generations of voters didn’t overtake the Baby Boom generation until 2018. Millennials now outnumber Baby Boomers as America’s largest generation, but the youngest millennials, at age 25, are just now old enough to qualify to run for federal office. The Constitution requires candidates for the U.S. House to be at least 25 and at least 30 for the Senate, and most candidates have prior experience before running for those big-ticket spots. They also need to build name recognition and a fundraising base. Because of that, even Gen X and Millennials are still lagging in representation.

That leaves Baby Boomers overrepresented in Congress, taking almost half the positions. And it’s also difficult to force older generations to let go of power if they don’t want to step down. There’s a strong incumbency bias for federal office, and the current structure of Congress rewards seniority, enabling longer-serving members with plum committee assignments to get more attention for their constituents’ needs. In the past century, average lengths of service for members of Congress have increased as members have become more likely to seek and win reelection.

The cost to run for office has also increased, and incumbent politicians have a huge fundraising advantage. In the U.S., the decision on whether to run for reelection is largely left to the candidates themselves. In countries with different systems, governing bodies can be more representative because parties can exert more pressure on candidates to leave and more effectively recruit younger members to serve. It may be that American voters aren’t electing younger candidates because they don’t have the options in front of them.

As Americans continue to live longer and longer, this may just be the future of politics. “I think, honestly, it’s up to older leaders to be self-aware enough to find the time to step aside,” Kole said.

Mary Radcliffe contributed research.